The Abyss of the Ocean

Cuban Women Photographers, Migrations, and the Question of Race

María Magdalena Campos-Pons. From the series When I Am Not Here / Estoy Allá. Tríptico I. 1996.

© María Magdalena Campos-Pons. Triptych of Polaroid Polacolor Pro photographs. Approx. 24 x 60 inches overall.

Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

“The Abyss of the Ocean lays bare the multiple Diasporic identities of Cuban women while confronting racist and colonialist stereotypes of their bodies.”

The Abyss of the Ocean: Cuban Women Photographers, Migrations, and the Question of Race focuses on identity and resistance through the creative practices of five artists living and working in the United States, Mexico, and Spain. The exhibition reveals the experiences and strategies of survival of María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Coco Fusco, Marta María Pérez Bravo, Gertrudis Rivalta, and Juana Valdés within the matrix of Latinx Art. Through their work, these artists challenge the concept of Latinidad and its relationship to Blackness in the modern/colonial project. Unsettling the totalizing definitions of Cuban, Latin American, and Latinx Art, The Abyss of the Ocean presents key photographic series produced since the 1990s. These photographs lay bare the nuance of the artists’ multiple Diasporic identities while confronting racist and colonialist stereotypes of women’s bodies.

The Abyss of the Ocean reframes a reductive, continental view of the Latinx identity to one that is fluid and archipelagic. For French Martiniquan philosopher Edouard Glissant, the ‘great’ narratives of the world (culminating in 19th century European imperial expansion) reduce complexity by emphasizing unification and totalization—a continental consciousness. In contrast, archipelagic thinking engages with exchange, fluids, mobility, and border crossings, and challenges the continental imaginary that perceives islands as fragmented and isolated. The Abyss of the Ocean employs the archipelago less as a geohistorical constellation of islands, and more as an “analytical framework to interrogate epistemologies, ways of thinking, and methodologies informed implicitly or explicitly by continental paradigms and perspectives.”[1]

[1] See “Contemporary Archipelagic Thinking: Towards New Comparative Methodologies and Disciplinary Formations,” Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, accessed January 14, 2021. See also Michelle Stephens and Yolanda Martínez-San Miguel, Contemporary Archipelagic Thinking; Towards New Comparative Methodologies and Disciplinary Formations (London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2020), pp. 1-44.

In Disturbing Categories, Remapping Knowledge (2019), art historian Tatiana Flores argues that the term Latinx has been narrowly associated with people of color (predominantly with Indigenous heritage) such so that Black artists of African descent have been consistently excluded in exhibitions curated from a Latin American perspective. This exclusion is made even more evident by surveying international exhibitions representing “Cuban Art.” Since the late 1990s, curators have explored the topic of race and racism in Cuba (notably, the ongoing project Queloides), exposing the marginalization of racialized bodies in the discourse of the nation-state. The Abyss of the Ocean should be understood in dialogue with these curatorial projects, inheriting their legacy and broadening it.

According to art critic Suset Sánchez, the particular silencing of Black women in the exhibition Ni músicos, ni deportistas (Havana, 1997) reflects a major paradox within the radical intention of the exhibit, given that Black women in Cuba constitute a demographic who have disproportionately suffered criminalization, objectification, and the racialization of their bodies. If the perspectives of women artists have scarcely been factored in the curatorial vision of these projects, an archipelagic perspective within a decolonial feminist lens further unravels the “entangled histories and affective connections that would otherwise be obscured by dominant and truncated narratives.”[2] Inspired by postcolonial Caribbean thought, a feminist archipelagic perspective centers racialized women’s experiences by foregrounding the aftermath of the abyss (of the slave ship, of the depths of the sea, and of the unknown). [3]

—Aldeide Delgado, Guest Curator

[2] See Yomaira C. Figueroa, “A Case for Relation: Mapping Afro-Latinx Caribbean and Equatoguinean Poetics,” Small Axe 61 (March 2020): 26.

[3] A more extended version of this curatorial statement was initially published by the Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture journal. See Aldeide Delgado, “What Does Archipelagic Thought Offer Toward the Understanding of Latinx Identity?,” Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture, April 2021, pp. 72-78.

Marta María Pérez Bravo. No son míos, 2008-2010. © Marta María Pérez Bravo. Courtesy of the artist.

No son míos

Marta María Pérez Bravo

Marta María Pérez Bravo’s creative practice marked a turning point in the documentary aesthetic of Cuban photography of the 1960s and 1970s. Pérez Bravo was the first artist who used her body in photography to not only deconstruct the idealized representation of motherhood in Western culture, but more specifically, to create a symbolic visual registry of the force of myths and spirituality in Cuban society. Previously presented in the exhibition Queloides. Raza y Racismo en el Arte Cubano Contemporáneo (Keloids: Race and Racism in Contemporary Cuban Art), No son míos (They Are Not Mine) constitutes one of the few artworks where Pérez Bravo directly addresses conflicts stemming from race. In these photographs, the artist overlays her portrait with images of Black subjects taken from police archives of the first half of the 20th century in Cuba—specifically, the images of santeros (practitioners of Santería) condemned in trials related to Afro-Cuban religions. Pérez Bravo conducted research in the colonial archive to chart the persistent strategies of control and surveillance by the state over racialized bodies, along with the stereotyping and increased criminalization of their civic activities and religious and cultural practices in the contemporary Cuban landscape. By superimposing these images, the artist not only breaks the idea of truth afforded the documentary apparatus but claims its performativity and its ability to acquire new meanings and symbolism under a prison state.

Marta María Pérez Bravo (b. 1959, Havana) is a Mexican-based artist whose work, mainly in photography and video, explores Spiritism, Christianism, and African-Cuban religions of Santería and Palo Monte from the lens of gender. Read more on the artist here.

Marta María Pérez Bravo. No son míos, 2008-2010. © Marta María Pérez Bravo. Courtesy of the artist.

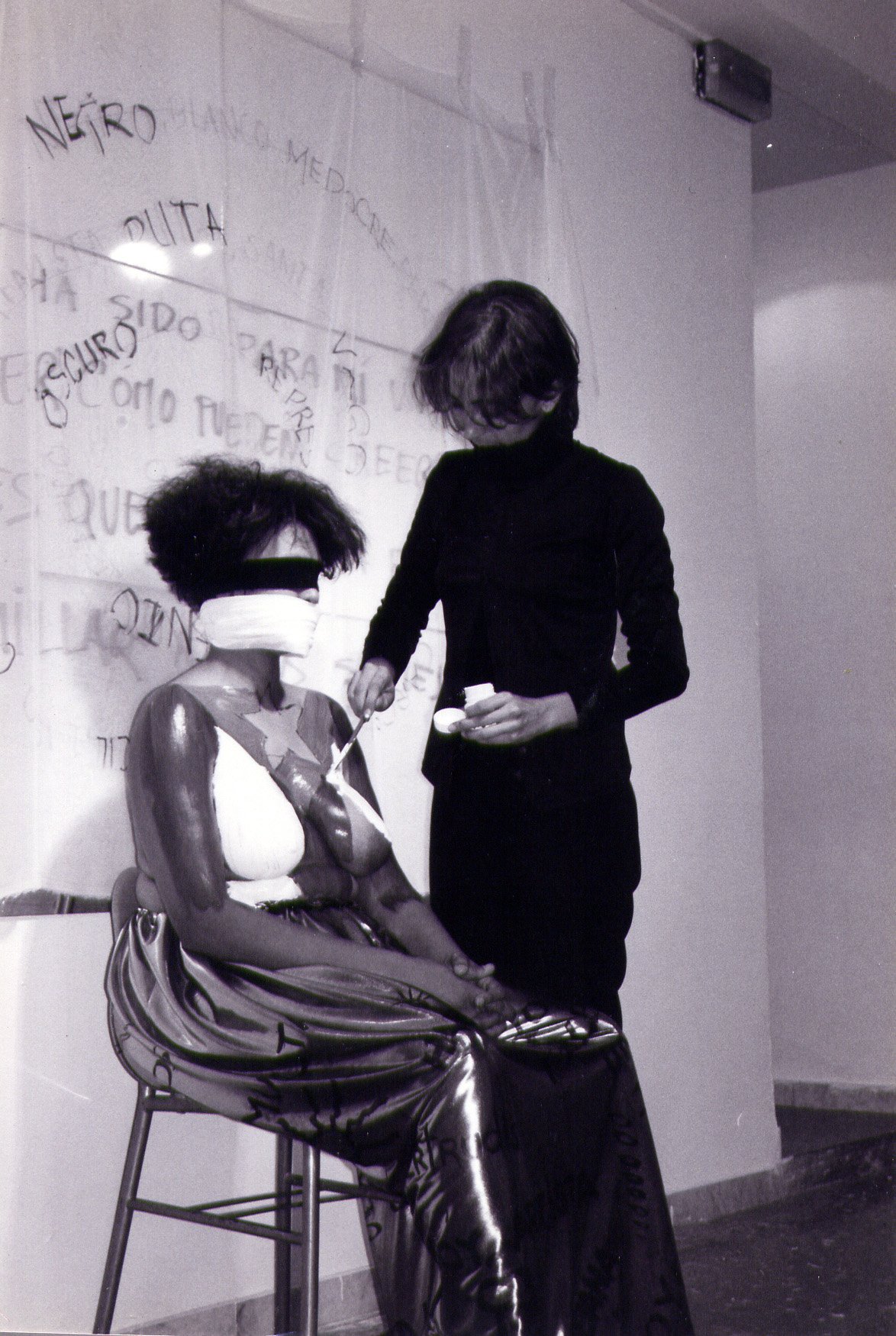

Gertrudis Rivalta. I (Yo). 2000. © Gertrudis Rivalta. Courtesy of the artist.

I (Yo)

Gertrudis Rivalta

Gertrudis Rivalta problematizes the archetypic invention of la mulata as an exotic and sexual object of the male gaze. She engages with a national and international oral archive that stigmatizes Black women’s bodies to first stage narratives of identity formation, and then deconstruct and distance herself from the oppressive forms that generate them. This is evident in the photo-documentation of the performance I (Yo), made while Rivalta was in an artist residency in Spain. According to her, this performance sought to criticize the judgment and stereotypes toward the bodies of Black Latina women. Rivalta’s work indicts the use of anthropological photos as a tool to justify the colonial project, by depicting Black individuals as inferior objects of study. These demanding images evidence the legacies of the abyss of the ocean that Edouard Glissant referred to while also expressing the vulnerability of Black women’s bodies and the many forms of violence they face every day.

Gertrudis Rivalta (b. 1971, Santa Clara) is a multi-disciplinary artist, living between Cuba and Spain, whose trajectory includes drawing, sculpture, painting, photography, video, and performance. Read more on the artist here.

Paquita y Chata Se Arrebatan

Coco Fusco

(in collaboration with Nao Bustamante)

Coco Fusco (in collaboration with Nao Bustamante). Paquita y Chata Se Arrebatan. 1996. Photography by Sven Weiderholt. Courtesy of the artist and Alexander Gray Associates Gallery.

Coco Fusco’s work challenges stereotypical representations of women and non-Western peoples in the media and in mainstream culture. Fusco also investigates the notion of “Latino” identity and the possibility of intercultural dialogue between U.S.-born Latino artists and Latin American artists. In 1996, she worked with San Francisco Chicana performance artist Nao Bustamante to create the fotonovela Paquita y Chata Se Arrebatan (Paquita and Chata Go Over the Top), which dealt with the cultural myths in the Western popular imagination that link Latin women and food to the erotic. Paquita y Chata Se Arrebatan was originally conceived for a special issue of the magazine Atlantica Internacional dedicated to Latin America. Fusco and Bustamante embodied the characters Chata and Paquita, modeled after dolls sold in folk art shops in the port city of Veracruz in Mexico. These paper mâché dolls depict coquettish Mexican sex workers as cute Latinas with dark, curly hair and their names hand-painted across their undershirts. Fusco researched the reemergence of prostitution, or sex tourism, in Cuba beginning in 1993 and its role as one of the most significant sources of income for women under the age of 25. She interviewed women and men involved in the business as sex workers and men who were involved as pimps. Informed by those experiences, Fusco and Bustamante approached Paquita y Chata Se Arrebatan as a way to think about the history of the representation of Latinas as sexpots.

Coco Fusco (b. 1960, New York) is a Cuban-American interdisciplinary artist, writer, and professor based in New York. She received her B.A. in Semiotics from Brown University (1982), her M.A. in Modern Thought and Literature from Stanford University (1985) and her Ph.D. in Art and Visual Culture from Middlesex University (2007). Read more on the artist here.

Coco Fusco (in collaboration with Nao Bustamante). Paquita y Chata Se Arrebatan. 1996. Photography by Sven Weiderholt. Courtesy of the artist and Alexander Gray Associates Gallery.

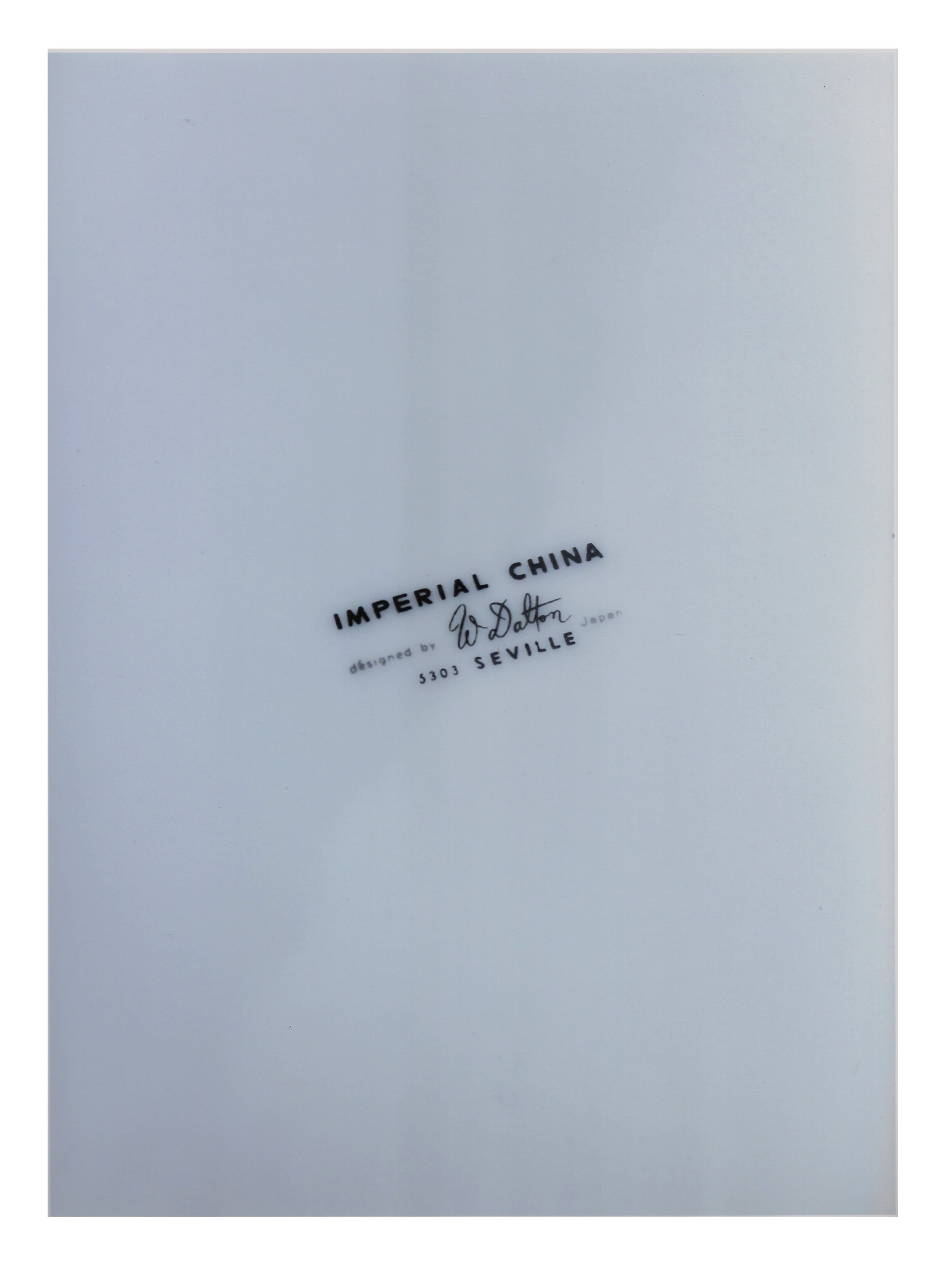

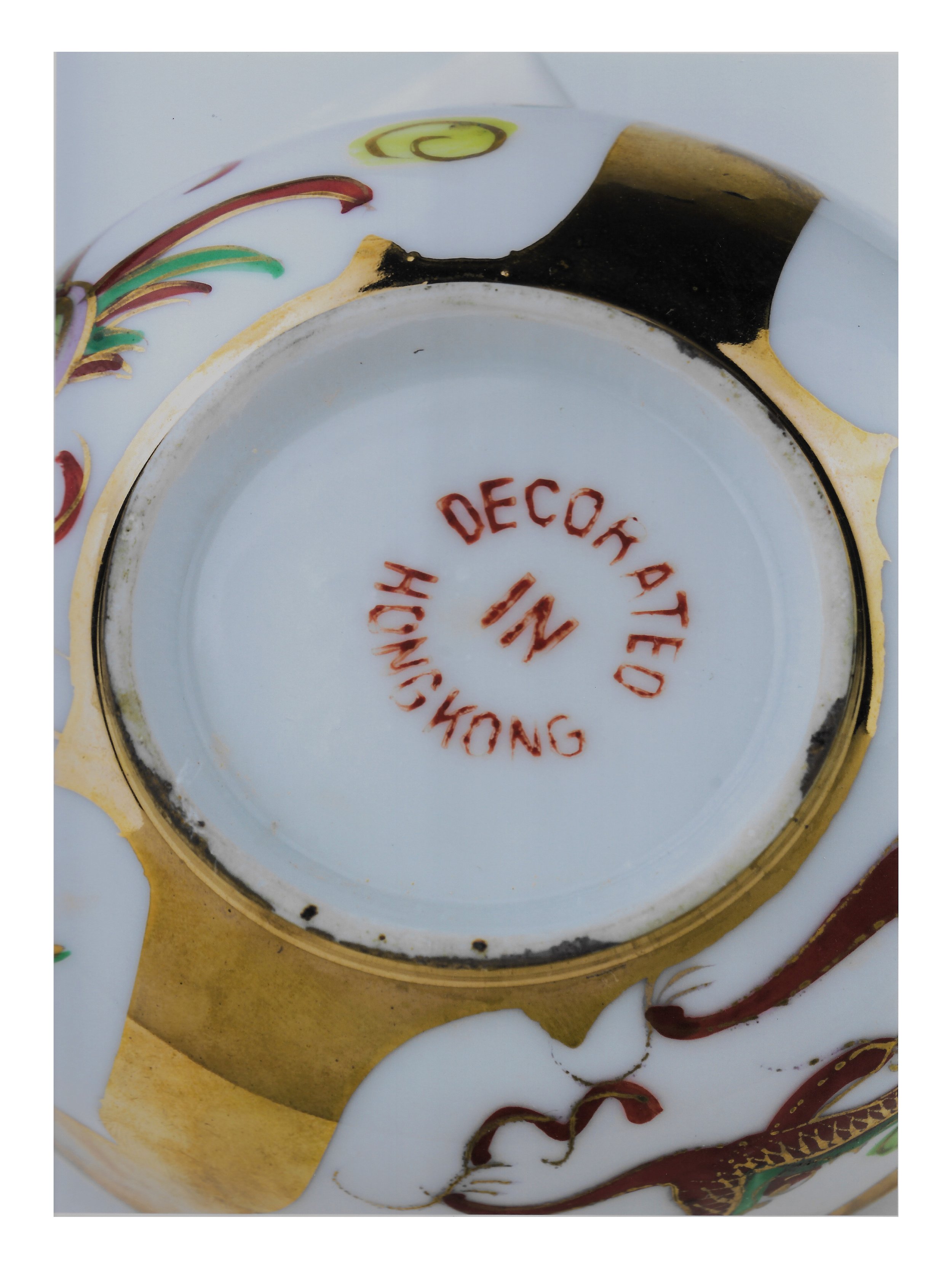

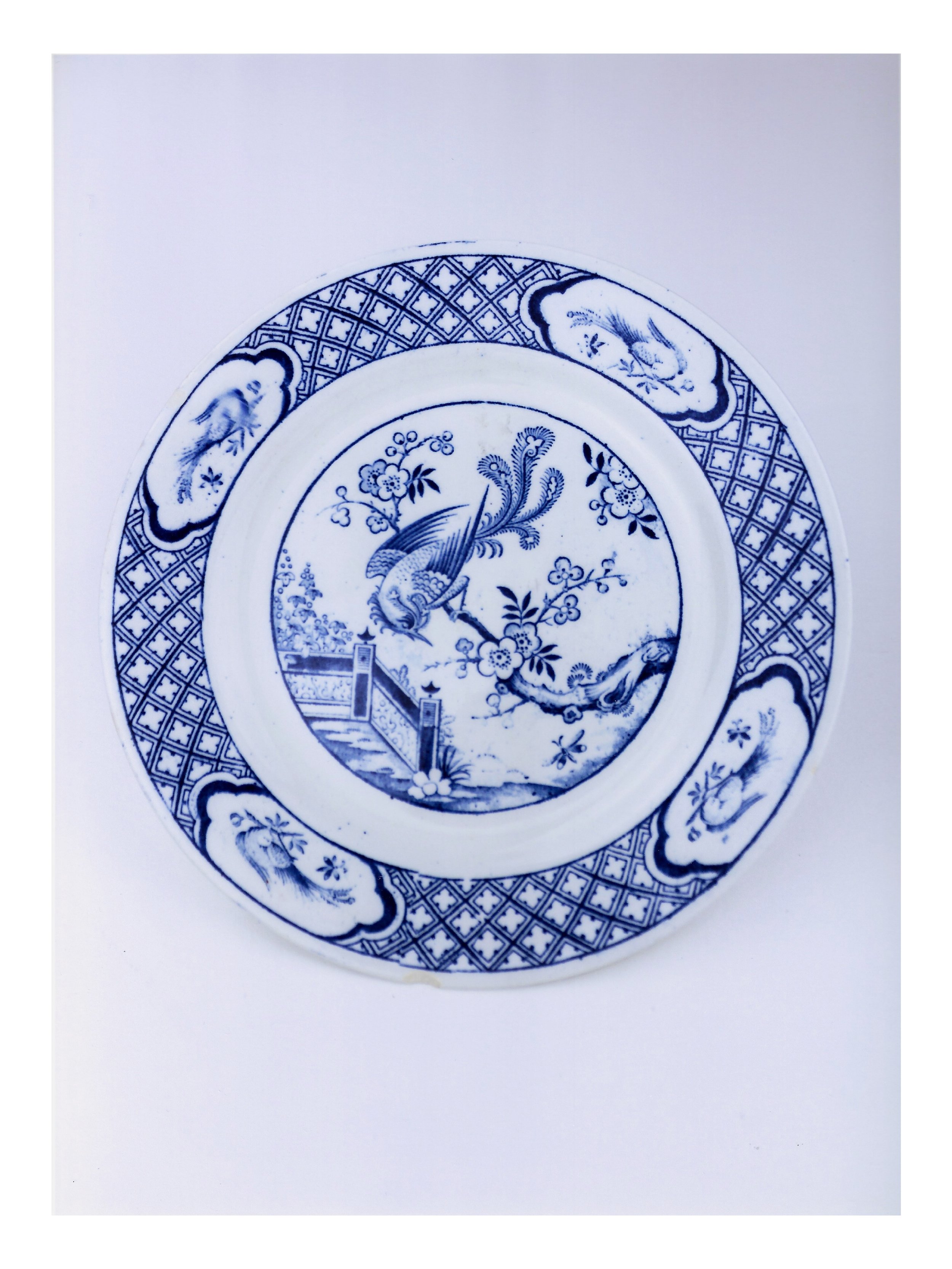

Imperial China

Juana Valdés

Juana Valdés. Imperial China, 2017. © Juana Valdés. Courtesy of the artist.

As a multi-disciplinary artist, Juana Valdes’s work collects, and records her own personal experience of migration. Her artwork is informed by her Afro-Cuban ethnicity and the experience of growing up in the United States. She examines the post-colonial history of the Americas and the current representation of Latinos, Caribbean citizens, and Blacks in mainstream institutions of power, reflecting on what is ascribed, contested, and granted. Functioning as an archive, the artist says, she researches the history and origin of objects that “map the complex terrain of multiple cultures and nations that constitute her own identity, and how it is constantly shaped and reshaped by experiences of displacement and transculturation.”[4]

Imperial China constitutes an installation of 55 images that catalog the front and back of mass-produced collectible ceramic objects. It traces the trading history of bone china, a type of porcelain appropriated from Asia and exported to the Americas as an economic commodity. In Valdés’ words, she uses “bone china’s natural property as a resource on which to build and extrapolate history as a material or a prefabricated resource. Whether purchased in real estate sales, auctions, or antique shops, these objects symptomize the ever-shifting cultural and economic values that are assigned by one race, gender, and/or class to another.”[5] Through her practice, Valdés questions the origins of the objects but also the body/hand that made them. This body/object relationship has become a recurring element in her work, associating the “deportation” of Black individuals of African descent, as a raw material and commercial good, with the massive violent expropriation of objects that began in the 16th and 17th centuries as part of the imperial discourse.

[4] Juana Valdés, “Artist Statement” (unpublished, 2019).

[5] Ibid.

Juana Valdés (b. 1963, Pinar del Río) is a multi-disciplinary artist and professor. She came to the United States at the age of eight in 1971. Valdés completed her MFA in Fine Arts from the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in 1993 and her BFA in Sculpture at Parsons School of Design in 1991. Read more on the artist here.

When I am not here, estoy allá

María Magdalena Campos-Pons

María Magdalena Campos-Pons. The Flag. Color Code Venice 13. 2013. Composition of 9 Polaroid Polacolor Pro photographs. Approx. 72 x 60 in. overall. © María Magdalena Campos-Pons. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons emigrated to the United States in 1991. She grew up on a sugar plantation in a family with Nigerian, Hispanic, and Chinese roots in the province of Matanzas, Cuba. Her work is autobiographical, investigating themes of history, memory, gender, and religion and how they inform identity. Here, the notion of identity is not fixed and monolithic, but a complex mix of heritages, multilingualism, and transnational migration. The artist herself, as well as her Afro-Cuban relatives, are often the subjects of her photographic compositions, generating images that claim space for women's issues while telling stories of those who have been relegated by the colonial matrix of power.

The photographs included in this exhibition reveal Campos-Pons’s artistic persona FeFA, which according to art critic and curator Octavio Zayas, stands for “familiares en el estranjero” (Fe) and “family abroad” (FA). FeFA is a metaphor of the immigration, exile, family, and community separation experienced by numerous Cuban families. Sometimes, the artist is a healer, a “maternal figure who brings blessings, casts out wrongs, and cleanses away bad spirits. [In other moments], she is imposing and demanding, angry and fearless, projecting the pain, the loss, and the survival of a [B]lack woman who can display the wounds and scars of her suffering and resilience.” [6] FeFA is aware of the performative character of identity and the marks of fragmentation, displacement, colonialism, and the stories of survival dating back to the slave trade, the sugar plantations, and to her exile experience in the United States.

[6] Octavio Zayas, “Becoming Fefa,” Altántica: Revista de Arte Moderno y Pensamiento, accessed January 28, 2022.

Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons (b. 1959, Matanzas) graduated from the National School of Art in 1979 and the Higher Institute of Art in 1985, both in Havana. She earned her MFA from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 1988. By the late 1980s, she gained international recognition as part of the emerging New Cuban Art movement. Read more on the artist here.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons. My Mother Told Me I Am Chinese: The Painting Lesson. 2008. Composition of 9 Polaroid Polacolor Pro photographs. Approx. 72 x 60 inches overall © María Magdalena Campos-Pons. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons. From the series When I Am Not Here / Estoy Allá. Tríptico I. 1996. © Triptych of Polaroid Polacolor Pro photographs. Approx. 24 x 60 inches overall. © María Magdalena Campos-Pons. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.